New Balance

A friend recently formalized this idea for me: as people who care about other people, we must be in balance in what we give and receive. If we give out more than we receive, then we will be depleted. I've been ineffective at receiving, seeking out too few good friends who can give back to me. At the same time, I've been both giving too much and ineffective at that too: enabling, rather than supporting.

The natural thing is to think: oh, I've gained insight into a problem, how can I fix it? This is good, and true, but one of the fun[1] parts of being a parent is that, when one discovers this kind of character defect in oneself, one actually ends up with a double mission:

- Fix it in yourself

- Make sure not to create it in your child

Somehow, that makes it easier. Maybe because I want to do it more for my son than I want to do it for me; maybe because I can look a little step-by-step at my son and his needs in a way I can't for myself.

The Balance Equation

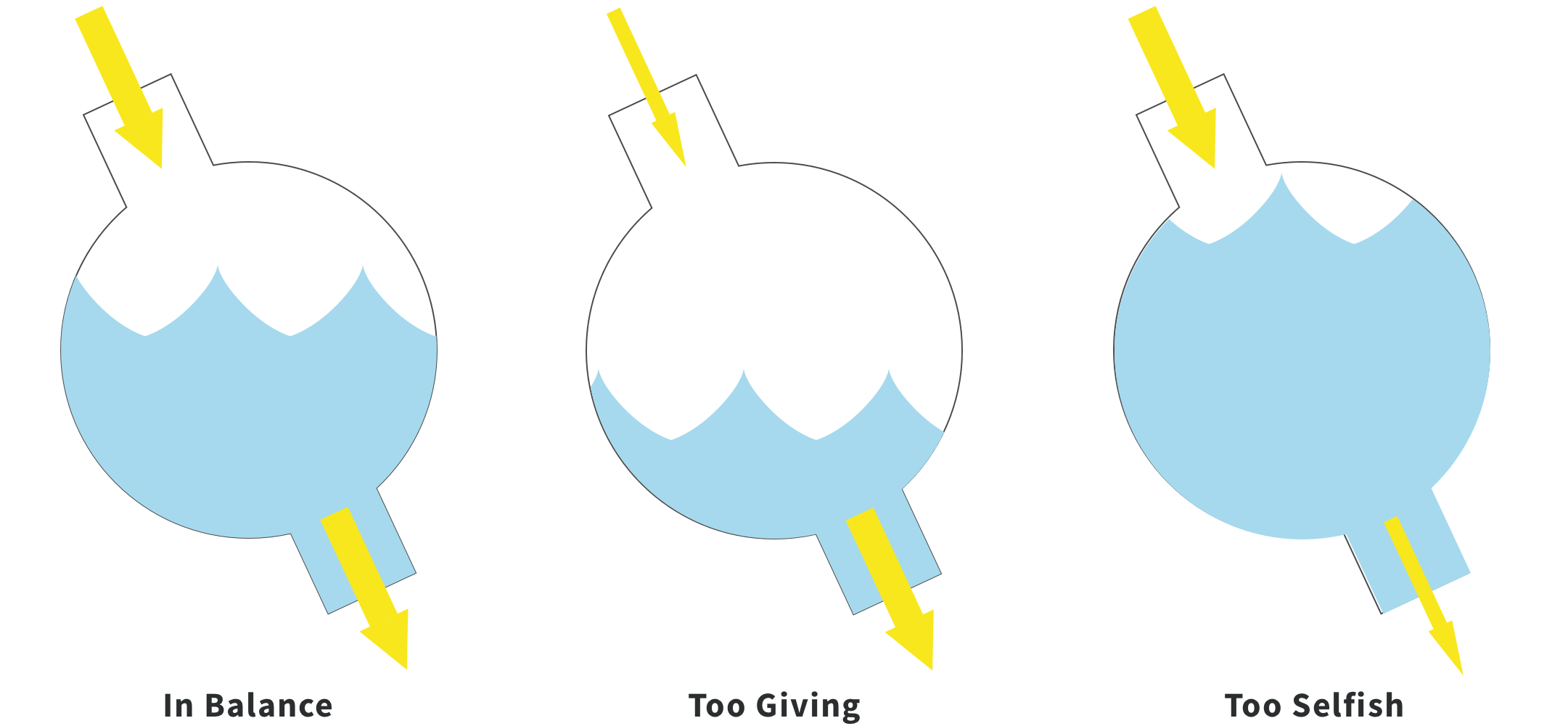

The way my friend described it is simple: we give from our heart, and we receive what others give from their heart. If we give too much, we have to draw down our own reserves, and we begin to feel empty inside.

The catch is: you don't gain from just any kind of giving, and you don't help with just any kind of taking. As someone not always good at boundaries, I spent years giving but not helping (and not getting much in return, either). I offered too much unconditional approval. But what should I have offered?

Dale Carnegie says: "In our interpersonal relations we should never forget that all our associates are human beings and hunger for appreciation." The somewhat less rah-rah-y William James echoed that when he said "The deepest principle in human nature is the craving to be appreciated." Appreciation is different from unconditional approval — it's honest to an individual's self and values.

Keeping the Right Stuff Flowing Out

Appreciation is key, of course, but there's more. Dale Carnegie points out "We nourish the bodies of our children and friends and employees, but how seldom do we nourish their self-esteem?" One component of building self-esteem is appreciation, but there's more to it than just that.

The key comes from No-Drama Discipline, when they say "connection isn’t the same thing as permissiveness." We don't give to others when we let them run their lives aground.

Nor do we give to others when we make our giving reliant on their overall perfection. Overall performance doesn't always matter: it's important to celebrate the small daily victories. Yeah, I'm quoting Dale Carnegie again:

Try leaving a friendly trail of little sparks of gratitude on your daily trips. You will be surprised how they will set small flames of friendship that will be rose beacons on your next visit.

We need to let others know what they've done well, what they've made us grateful for, every day. I've actually started tracking my gratefulness every day, so that I can be more aware of what I am and am not appreciating. It's amazing how often someone unexpected comes up in that list. Now, my challenge is to let them know.

Keeping the Right Stuff Flowing In

When I outlined this post, this was the natural section to put next, so this heading is here. I'm not particularly sure I know how to answer this question.

I've been lucky to make a few new friends who are interested in giving as much as they get. A few of my oldest friends are also able to give. Hopefully, I'm showing them all that I can be as giving — and as giving in a useful way — as they are.

But, I have a lot more to learn here. I'd appreciate any suggestions of resources in learning how to care for oneself in friendships. I've got some Brené Brown on the reading list, but that's just a first step. Books, podcasts, blogs — I'd love it.

What Should Flow Out to my Son

Obviously, one's child is a special case of keeping the right stuff flowing out. Not only do I owe my son the best treatment, but I also have the opportunity to model (and, thus, live!) the way he should behave to others. So, The Whole-Brain Child's words stand out:

Rather than ignoring their big emotions or distracting them from their struggles, you can nurture their whole brain, walking with them through these challenges, staying present and thus strengthening the parent-child bond and helping your kids feel seen, heard, and cared for.

Being giving to my son — that means recognizing he's not a grown person; that he needs to learn how to deal with his experiences and his emotions; that he needs to feel actualized and loved; and that I'm just the man for those jobs.

In more specific terms, as The Whole-Brain Child says, "with every fun, enjoyable experience you give your children while they are with the family, you provide them with positive reinforcement about what it means to be in loving relationship with others." I can give those experiences by following the advice from No-Drama Discipline, that "part of truly loving our kids, and giving them what they need, means offering them clear and consistent boundaries, creating predictable structure in their lives, as well as having high expectations for them."

But, Balance

My son should, and can, expect me to do all of these things. But, balance says that no relationship can go in one direction — even if it's with a 3-year-old. The great thing about being a father is that the more I invest in my relationship with my son, the more I'll get. At this amazing age, my son has truly discovered how to express his love. He hugs me, tells me he loves me, wants to wrestle and cuddle and play blocks together. The more time I spend with him, the more I make sure that time is great by setting appropriate boundaries and creating good traditions and structures, the more I reap this.

At the same time, I can also invest in receiving more rewards from this relationship. At his developmental level, my son is still beginning to learn what his emotions are, and become able to express them. If I want him to be able to express love — or, for that matter, negative emotions like anger and frustration, which are just as important to learn to express — I need to give him those tools. The Whole-Brain Child advises: "take time to ask kids how they feel, and help them be specific, so they can go from vague emotional descriptors like “fine” and “bad” to more precise ones, like 'disappointed,' 'anxious,' 'jealous,' and 'excited.'"

At his developmental level, my son is still mostly at the mercy of what some call his "primitive brain", "fast brain", or "hot brain": the impulse-driven, quick-reacting, fight-or-flight part of cognition.[2]

Not to put down a cute 3-year-old, but this is not the most fun kind of person to be with, day in and day out. We all have our party friends, the most fun (and often the most caring!) when you want to go out, but no good when you need a problem solved or just a quiet night in. Well, a toddler is this friend all day long, every day. Not only do I want my son to pass the Marshmallow Test for his own long-term success, I want him to pass it so that I can not be subjected to wild toddler mood swings and unfocused energy. Back to The Whole-Brain Child here:

Do you want to trigger reactivity in your child’s primitive brain, or engage her thinking, rational brain in being receptive and openly engaged with the world?

I want the latter. It will be better for my son, and vastly more fun for me. So, in balance, I get love, and I get a great person to be with, and all[3] I need to do is show love and build boundaries.

I started on this path because I was worried that my discipline style was too aggressive. For the purposes of wrapping up that story, I can learn to "discipline in a way that’s full of respect and nurturing, but that also maintains clear and consistent boundaries," in the words of The Whole-Brain Child. "When parents offer repeated, predictable experiences in which they see and sensitively respond to their children’s emotions and needs, their children will thrive— socially, emotionally, physically, and even academically," they go on to say.

So, my giving — my positive giving — is love, boundaries, talking about emotions, and more love. I can do that. That sounds joyous, and giving, and, most of all, kind to us all.

I shall pass this way but once; any good, therefore, that I can do or any kindness that I can show to any human being, let me do it now. Let me not defer nor neglect it, for I shall not pass this way again. — Dale Carnegie